Written by Peter Kray

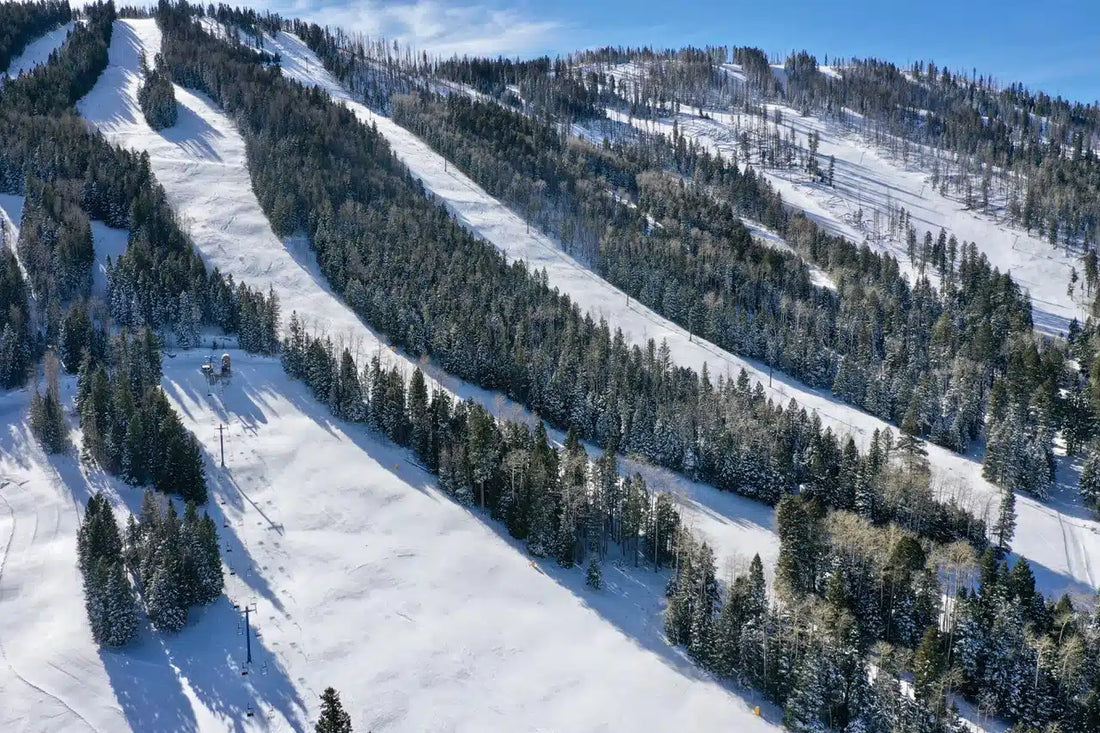

If you have ever driven Hwy 285 from the little town of Antonito, Colorado, to Santa Fe, New Mexico, you have seen the steep, diving ski runs of Pajarito Ski Area.

“The Little Bird,” as locals call it, features a relentless face of black and double black diamond runs that drop straight from the summit to the base with hardly a dogleg or curve. “It’s surprisingly steep!” my friend Erik said. “Like a baby Taos Ski Valley with huge views of the Sangre de Cristo Range to the East.”

When I moved to Santa Fe from Colorado, I thought Taos was the only ski area in the state and that I would be living in a flat, hot desert. But wherever the red-haired girl went, I would happily follow her across the planet.

What I didn’t know is that Santa Fe sits at 7,000 feet and is the highest capital city in America. Founded in 1610, it is the second oldest Europeanized city in the country, right behind St. Augustine, Florida, so it isn’t hard to imagine how if things had turned out a little differently, we might all be speaking Spanish.

I also didn’t know that Ski Santa Fe, where I have had a season pass for more than 25 years, has a base elevation of 10,350 feet, just one hundred feet lower than the summit of Jackson Hole Mountain Resort.

I remember imagining myself as some intrepid explorer staring up at the shimmering, untracked fields below Tesuque Peak, telling my neighbor, “Johnny” Juan Herrera, a D-Day veteran who earned two purple hearts fighting his way off Utah Beach, that I was going to climb up there to ski the fresh powder.

“Well, I’m not telling you what to do, Pedro,” Johnny said. “But you could just ride the lifts.”

Secret City

My first job in Santa Fe was stuffing promotional envelopes for the American Spirit Cigarette company and writing the occasional freelance story for SKI, Powder, and Couloir.

Then I got a job tuning skis at Alpine Sports, a high-end ski store owned by New Mexico Ski Hall of Fame members Harvey and Reserl Chalker, who treated their customers and employees like an extended family of gravity addicts. Every morning I walked under a photo of Reserl on the cover of Skiing Magazine taken when she was racing for Germany in 1961 on my way to the shop.

The season was winding down when Catherine ran uphill to catch a friend and me walking down West Coronado Road with a case of beer to tell me the Los Alamos newspaper was hiring a reporter to cover crime, business, and schools.

My dad always told me I should get a job at a paper. I told him I wanted to be a novelist, and that writing news would “ruin my style.”

But he was right. I took the job and every day started at the police station reading the crime report, then back to the paper, which had an afternoon delivery cycle, where I had to produce a freshly reported story about something, anything, by three p.m. Nothing like a deadline to make you write.

I also began to find my people. The police captain and his wife who had us over for dinner, with dogs everywhere, and sitting on the edge of the table, a large cockatoo. The record shop owner who would keep an ear out for Gram Parsons bootlegs. And skier Dean Cummings, who learned to ski at Pajarito before beginning a career that would take him from the mogul tour to running a heli-ski operation in Alaska.

There is another story about Dean, but he was exonerated of that. And it’s the ski stories I remember the most. Although there was a time just before the incident that landed him on the front page of all the Northern New Mexico newspapers that I stopped taking calls from the 907-area code.

Skiing the Secret

Los Alamos is a muted city, a company town for the Los Alamos National Lab (LANL) with neighborhoods separated by beautiful canyons of ancient stone. There is a sense of caution in the air because so many people have a Q Clearance for all the restricted data and nuclear material they access. I earned an Associated Press Award reporting on the influx of heroin there when no one would talk about what this “new drug” really was.

Pajarito’s history coincides exactly with the Manhattan Project in 1943, when expats and scientists including J. Robert Oppenheimer, first started The Los Alamos Ski Club at Sawyers Hill, skiing away, perhaps, from the knowledge that the nuclear weapon they were building would change the world.

When snow got low close to town, the area was moved to Pajarito Mountain. The legend is the Army Corp of Engineers cut the runs, almost equidistant across the slope. And although I do believe there is a grooming machine, I’ve never seen it.

My friend Mike, who is a walking encyclopedia of New Mexico ski history, maintains that the ski lifts might still be the town’s biggest secret.

“When I was in high school in the early 1960s, Los Alamos was very protective of their ski area. There was absolutely no signage anywhere indicating how to get there. You just had to know,” Mike said.

Working at the paper, I learned to telemark there on the long, steep bumps. And rode my snowboard for the last time on a lift, preparing for a trip to Island Lake Lodge with Burton Snowboards where it quickly became obvious I was a skier at heart.

This past President’s Day weekend, some 20 years later, I finally went back. I had a ski buddy in town and Ski Santa Fe was packed, so we ventured back to Pajarito, and found ourselves far off the beaten path.

There are no bars at Pajarito, either in the lodge or on the lifts. Old chairs rise high over the runs like rusted Impalas with no seatbelts. People wear the same parkas they probably wore when they moved there, and the lifties smile as they scan your ticket. “Are you having a good day?” they ask.

My friend Mark and I sang 70s songs to each other, embracing the sense that we had fallen into some kind of alpine time warp. We took pictures of the great three trunked aspen tree beneath the Aspen lift, glowing in the clouded glow of the sun like something out of Middle Earth. And stopped to talk to the Malamute on the deck who would howl anytime he wasn’t being pet.

The truth is, after two decades of skiing resorts around the world, Pajarito made me feel a little soft. The wild empty trails and ungroomed glades where it would still take days to ski out the snow. The tiny guardrails on the winding road with full consequence drop-offs. The mud parking lot.

In bed that night, going over the best turns of the day, I felt I had survived something raw and half-forgotten. Some cold, windswept sense of soul, really. And now I can’t wait to go back.