The writer, horseman, and Mountain Gazette contributor on the culture and work of the West’s true cowboys—and why it will never die.

By Hannah Truby

Calloused hands. A horse’s nature. The West’s expanse. The work and culture of the true cowboy is something Will Grant knows well. As both a horseman and a writer, he brings a quiet certainty and lived perspective to the world he writes about. His story “Good Work”, published in Mountain Gazette 204, reads like both an elegy and a celebration: a tribute to the true working cowboy and a meditation on a way of life that refuses to disappear, no matter what the world believes.

The story appears alongside images taken by the late David Stoecklein. “David was a pioneer in cowboy photography,” Grant says. “I grew up seeing his work in the ’90s, and I wanted to write something that would accompany that kind of imagery.”

Stoecklein’s son—a former sponsored skier turned photographer—and Mountain Gazette editor Mike Rogge approached Grant with the idea, pitching it as a kind of antithesis to Taylor Sheridan’s hyper-dramatic Yellowstone, a show as widely embraced by outsiders as it is derided by those who actually know a thing or two about ranch life (see Washington Post’s “Why real cowboys see ‘Yellowstone’ cowboys and just have to laugh”).

“I don’t like positioning it as something so negative,” Grant says with a dry laugh, before adding, “But I’m definitely not watching that shit, either."

Vivid in its description of both the elements and the labor, “Good Work” pays homage to the men and women who keep doing the work—honoring those who stay without condemning those who leave.

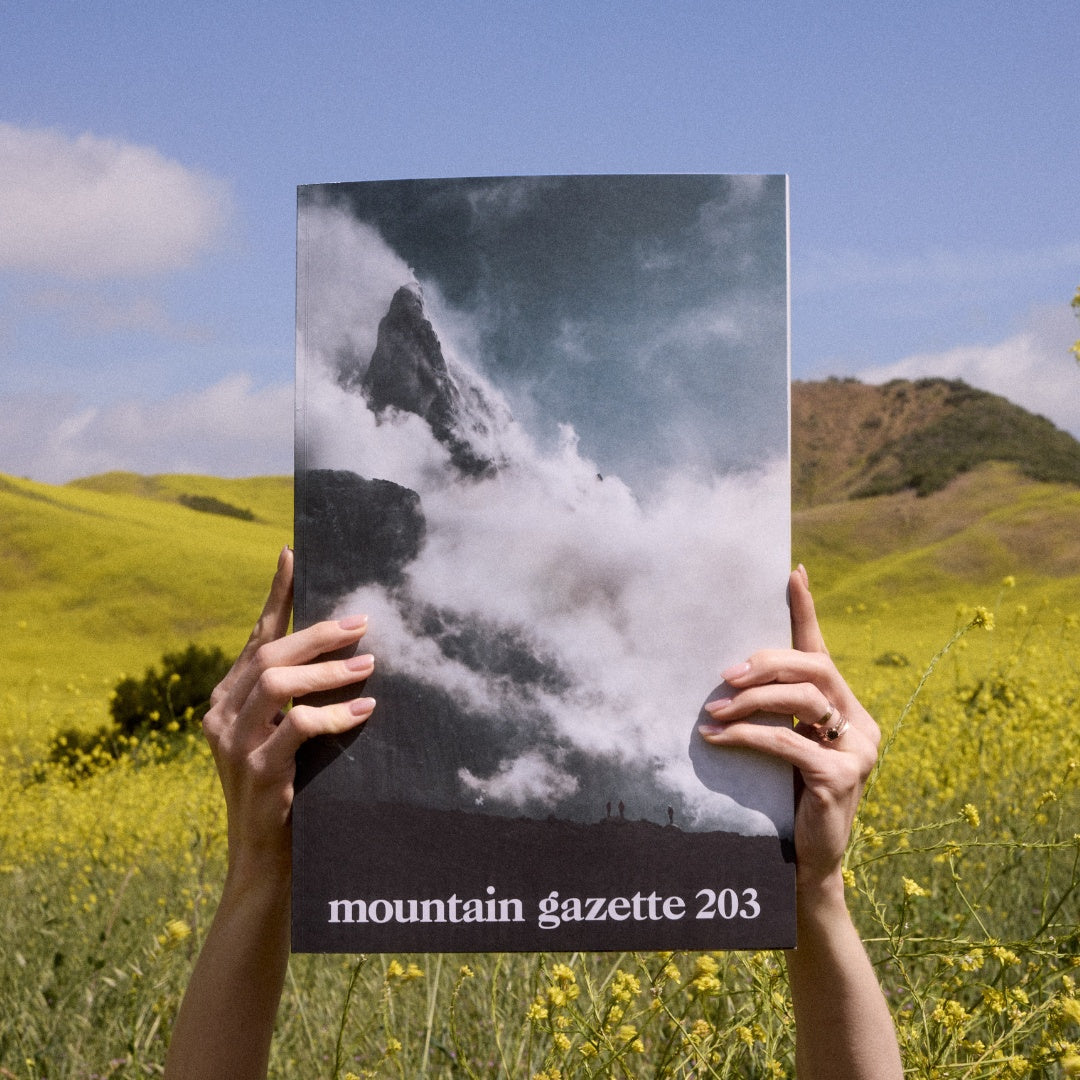

Photo by David Stoecklein, from Good Work by Will Grant (Mountain Gazette 204)

Because, after all, a cowboy’s work is arduous, and the essay notes that many eventually leave it behind to “do what everyone else does. Go to work at a laptop. Check email rather than newborn calves.” To them, Grant offers a kind of benediction: “You did the right thing. You went home, left the bleeding on the mountain to someone else, and it’s probably just as well.”

In that way, “Good Work” feels like it has a point to make—but Grant doesn’t care much whether or not it’s taken.

That cowboys are a “dying breed” is a false yet widely circulated narrative, Grant writes, one that sells to the public because it fits neatly with what many people want to believe about the 21st‑century West.

“People often assume that traditional ways of working with horses or livestock are disappearing—like the true Mongol horsemen or cattle drives in Kansas. But that’s not true,” he says. “There will always be people in the West who want to live that life. ATVs and motorcycles have changed cowboy work, but it’s never going away. Letting people believe it might actually make them value cowboys more—it casts the culture as something rare and worth appreciating.”

This, he explains, is what fuels his writing.

“There’s so much about this aspect of the Western half of the United States that is special and noteworthy,” he says. “The relationship between humans and horses is real and meaningful. There’s a vocabulary, a way of looking, that’s a product of the land and history. The cowboy is like this distinct subspecies, with mythology and romanticization behind it, which is what motivates me to write about it,”

Grant spent years as a cowboy and horse trainer before he began his journalism career. While he still works as a cowboy—owning five horses, two dogs, and three chickens at his Santa Fe home—his recent years have been devoted more to writing about work life, a shift he calls a “pretty natural transition.”

Both as a cowboy and as a writer, Grant has seen much of the West. For his first book, The Last Ride of the Pony Express, he rode 2,000 miles on horseback across it. When I ask if one place stands out, he doesn’t hesitate.

“Eastern Nevada,” he says. “Around Wells and the town of Eureka. It’s beautiful, sparsely populated country—good grass, wildlife, nice people. I could ride all day without seeing anyone. It hasn’t changed much. That’s rare.”

Now, Grant is at work on a new book tracing the ancestry of the cowboy—from the origins of his vocabulary to the lineage of his horses. “I’m basically trying to reconstruct where everything came from,” he explains. “From the way he talks to his equipment, to how horses spread through the West.”

As our conversation winds down, Grant reflects on the cowboy’s enduring appeal and the resilience of the work itself.

“The cowboy life, and the stories that come from it, are still alive,” he says. “It’s worth paying attention to the people who keep it going.”

While some enter the line of work and others move on, “Good Work” makes one thing clear: the cowboy way of life persists. “The beauty of the landscape is in its dearth of people, and the cowboy line of work isn’t going anywhere.”