June 25, 2005

Cache Bar, Middle Fork of the Salmon River take-out, Idaho

Her eyes follow me as I row toward the boat ramp, and a ghost-like feeling from years ago creeps up my spine, icy and tentacle-like. It’s like when Billy died. No, it’s not that bad. Can’t be. I couldn’t take it if it were.

The girl sits atop a granite boulder onshore. She’s small, blonde and pretty, maybe nine or ten. She’s wearing a floppy sun hat that would make her unbearably cute except for that scary, children-of-the-corn look on her face. Must be with the private rafters de-rigging on the ramp. I meet her gaze and force a grin, and she snaps back with a start, as if waking from a bad dream. Her mouth turns upward at the corners in a mechanical smile, but the sadness never really leaves her big, blue eyes.

All the privates and the other commercial guides are looking at us like that, watching as we slowly break down the trip. A trip that was great until the final minutes. You know they all care, they mean well, but you just wish they’d stop staring at you like you’re the fucking Elephant Man.

The ramp is the usual cluster, minus the normal sense of happy, organizational bustle. Instead, the place is like a losing football team’s locker room. The ambulance is gone and the bus took most of the guests back into town for showers, a change of clothes and phone calls to loved ones, during which they’ll process their grief, saying you wouldn’t believe what just happened, we watched it all go down, it was horrible. But we, the boatmen, have to de-rig the rafts and load the trailer, dump the groovers and trash, and get back to Salmon ourselves. The work keeps us busy, which is good, but all we really want to do is sit down under a tree, hang our heads, and sob. Management sent two off-duty guides to help us, and thank goodness for that. Without their help, we’d be here until dark doing what should be a one-hour job.

By the time we finish loading, the seven of us are among the last people on the ramp. Frank, a grey-haired, old-school Grand Canyon and Middle Fork guide, greasy cowboy hat and all, reaches into a cooler on the back of the trailer and extracts a mostly empty bottle of Captain Morgan. “Bad luck to bring back un-drunk liquor,” he says, taking a pull. He removes his hat, revealing a bald, sweaty pate, wiping his forehead on his sleeve. Bottle held limply at his side, he wags his head, an empty gaze directed at his feet. “Goddamn,” he mumbles, “I’ve had a smoke and a shot of rum and I still can’t get the fuckin’ taste out of my mouth.”

I cringe at this because I taste it, too. I don’t know if it’s my imagination, or the taste of my own blood from cut and bruised lips, or the stale air I inhaled while helping Frank try to breathe life into a man, a husband, a father of two lovely daughters. But it’s definitely there: sickly and stale, nauseating. The taste of loss. Something I really don’t need. Not now. Not ever.

June 20, 2005

Boundary Creek, Middle Fork put-in, Idaho

Boundary, like most popular river put-ins, is a place where you seemingly always run into old friends and acquaintances, at least you do if you’ve been in the river-running culture for a couple of decades.

The night before our first launch of the season, I caught up with Jane, a long-time friend from South Africa, and a fellow guide. She was working in Idaho for the summer, taking a break from her other rafting job on the White Nile in Uganda. We spent the evening talking about our lost loved ones (her dad had just passed away), lost loves (I’d just lost my girlfriend) and the inevitable discussion about why we, two supposedly intelligent people entering middle age, were still guiding — and still single. Was it a calling? An excuse to avoid real life? The only thing we knew how to do? Ten years of talking about it and neither of us was any closer to an answer.

But the river heals all. At least that’s the cliché I’d like to believe. Most of the time, it works, anyway. I’d just come off a Grand Canyon trip where I had 18 days to process the recent heartbreak. But when your partner dumps you by email (while you’re off skiing in Switzerland), then promptly moves out, gets engaged to a much younger guy and announces she’ll never see you again — all within five weeks — well, even running Lava Falls and watching two billion years of geology drift by can only do so much. It was better than self-medication through drinking at least. Though I’d done a lot of that lately, too. Unlike the river, booze generally doesn’t help. But sometimes a little self-destruction is all you can manage.

Rigging paddleboats on put-in morning, I ran into some folks from back home in eastern Idaho, launching their own float trip. They asked about my winter and I told them about the ski trip, the break-up, the Canyon. They then decided to fill me in on my ex’s activities during my time abroad — like seductively hanging on every guy in the bar at the local ski hill. So much for Grand Canyon therapy. Where’s a fucking gin-and-tonic when you need one?

My new round of self-pity was cut short when a school bus rolled in, spewing forth our guests for the week. They were a pretty typical group: an abundance of married folks in their fifties and sixties, a handful of kids and exactly one blonde 19-year-old girl, whom the all-male crew had anticipated, having spotted her “stats” on the trip roster. We do that, you know, scan the guest list for females of desirable age, height and weight. Yeah, we’re pigs. Not that our lechery gets us very far. Nowadays, they’re all old and married, or almost a kid, like this one.

We promptly put our folks to work, forming a fire line to load gear onto the boats. I positioned myself between the rafts and a string of guests headed up by a pudgy, middle-aged guy who seemed none too steady on his feet. Nothing unusual there, as our guests tend to be that cross section of America who work behind computers and get most of their exercise dodging salads. Wow, I thought, this guy’s getting winded just standing there, even before he starts trying to huck fifty-pound dry bags around. Must watch him this week. But then he boarded one of the oar boats, I captained a paddleboat the first day, and with 23 guests to get acquainted with, I almost forgot about him.

His name, it turns out, was Steve. By the end of the trip, I’d never forget him.

Steve’s daughters did get in my boat that first day. Jean, the 19-year-old, was a cute, smart, articulate college student. Physics major, no less. It turns out that her not-so-steady dad was a 51-year-old nuclear scientist at Los Alamos. “But the real brain is Teri,” Jean said on the boat that afternoon, nodding at her sister, a freckle-faced brunette with the self-conscious smile of a 15-year-old stuck with braces. “She’s the math whiz,” Jean said. Given that dad was Doctor Science and Jean obviously no slouch, I safely assumed teen-aged Teri could out-calculate my dirt-bag, raft-guide ass in her sleep.

The first day, we pulled some miles, getting into camp late. After slaving over a hot grill, carefully preparing “Burnt, Raw Chicken in The Dark” (as the crew was fond of calling it), I pulled up a camp chair on the beach to read “The Kite Runner,” a popular tear-jerker set in war-torn Afghanistan. Teri and Jean sat nearby to read as well. It turned out Teri was also reading “The Kite Runner,” while Jean enjoyed D.H. Lawrence’s “Sons and Lovers.” Over the course of the six-day trip, we had something of an informal book club going, spurring some nice conversations in between the guides’ mandatory beer-drinking sessions.

I noticed that Steve, his wife Mary, and their daughters were unusually close-knit. Nineteen-year-olds simply don’t camp right next to their parents and little sister on these trips, but Jean did. They slept side-by-side under the stars when the weather was good, and in adjacent tents when it wasn’t. Also on the trip were three close family friends, including a fun, personable couple heavily into bird watching and a guy named Arnie, a perpetually cheery fellow always ready with a kind word and a hearty laugh. They were low-maintenance folks, thoroughly enjoying the river, the scenery and each other’s company, despite persistently rainy weather.

It wasn’t until the fifth day that I had occasion to chat with Steve, and then it was an unsettling conversation. I stood with coffee mug in hand, waiting in line behind Jean to use the groover — our portable toilet — at Survey Camp. We were chatting amiably when I noticed Steve struggling across rocky terrain twenty yards away. His head was listing to one side, as he stood with a helpless look on his face, afraid to move. He weakly called Jean’s name and she ran to him, her cheery morning mood instantly turning serious. I started to help, but thought better of it, not wanting to embarrass Steve. Jean helped him across the rocks to where I was standing and leaned him up against a ponderosa pine. She left to use the facilities, leaving me with her dad, who manually supported his own head as he leaned on the tree. Steve, sensing the awkwardness of the moment, explained he had a muscle control issue that would be okay after taking medication. “The wheels came off about three years ago,” he said, between clipped, shallow breaths. He described how he’d endured three lung cancer surgeries, lost part of his lungs and diaphragm. “It sucks,” he summarized, staring at the ground. Arnie later told me Steve was a fairly serious road cyclist before he got sick. He had become shadow of his former self, in the physical sense at least. I listened sympathetically, not knowing how to offer support, my thoughts drifting back to the painful memories of my own family crises: my mother’s lost battle with cancer, my father’s excruciating, prolonged death from AIDS. I offered to take him on my oar boat for the day, the only gift I could think of under the circumstances. He said that would be nice, looked me in the eyes and smiled. “I’m so glad the girls are having a great time on this trip. Thanks.”

After Jean returned and helped her father back to their campsite, I approached our trip leader, Neal, and Brandon, another senior guide for the company. I described the encounter and discussed Steve’s condition. They had recently heard the story from Steve as well, and seemed appropriately concerned. Shockingly, Neal said we had not received any medical info on Steve prior to the trip, which left me wondering if that was the result of a bureaucratic snafu or a deliberate omission by Steve and his wife to insure his participation on the trip.

As I finished rigging my boat that morning, Steve walked steadily down to the shore with the other guests, looking okay. He said he would be riding in Neal’s oar boat for the day, as he had a rigged a backrest for him. No worries, I told him, glad to be free of the responsibility.

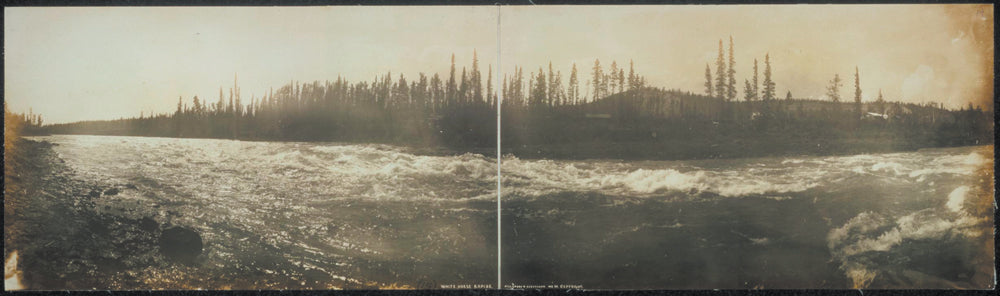

The sun emerged in all its glory as we floated into Impassable Canyon, always my favorite part of the trip. The river flows deep and green between towering walls of granite and the rapids gather energy, the Middle Fork swelling with each new tributary. A couple of our inflatable kayakers spilled and swam in the bigger water, but nothing serious. The melancholy of my recent heartbreak wouldn’t quite let me go, but at least I could feel the Middle Fork working a little river magic. I come back year after year for that dose of positive juju: the surging power of moving water, the refraction of sunlight in its depths, the subtle excitement of an upstream breeze blowing spray across the cresting waves. I also see that magic in the people around me. That’s what guiding is, I suppose — constantly reliving and rediscovering the wonder of rivers, through others and in your own heart, every time you’re out there.

On the final day of the trip, we ran the last of the major drops on the Middle Fork. The inflatable kayakers eventually gave up and boarded the rafts, tired and chilly in the morning shadows of the deep canyon. As we reached the confluence with the Main Salmon, our flotilla of seven boats had only one remaining rapid to run: Cramer Creek. It was also the biggest and most unpredictable drop of the trip.

Forest fires during previous seasons had stripped much of the surrounding high country of its forest cover. Over the following years, powerful thunderstorms caused numerous creeks to flash flood, emptying massive volumes of boulders, sediment and trees into the canyon. In some areas, the entire river was temporarily dammed, drowning major rapids beneath temporary lakes. As the relentless river carved away this alluvial debris, new rapids formed, the biggest of which was Cramer, sometimes called “De-rig” rapid, located on the Main Salmon just above Cache Bar, the take-out. Like any young rapid, Cramer was rapidly evolving, as water levels changed and high water tumbled unstable boulders in the channel.

Guiding a paddleboat, I followed two oar boats across the flat water above the big drop. I was a bit anxious, as my crew included Jean, Teri and some younger kids. It wasn’t the strongest crew, but at least they were healthy and enthusiastic. I thought Steve and his wife Mary had chosen wisely by riding in Neal’s oar boat, a decidedly more stable platform. Neal was out in front, leading our little flotilla toward the rapid and take-out, about a mile away.

As the thunder of Cramer became audible, a horizon line appeared before us, the pulsing turbulence of the rapid’s gut occasionally leaping into view beyond it. I steered my raft toward the right bank for the scout. I had not seen Cramer since the previous July, and was wondering if high water had changed it once again. But Neal wasn’t pulling over. I thought that unusual, but he and most of the crew had been down the week before, so I guessed he felt okay to read-and-run. Reluctantly I followed, rather than foul the boat spacing and get left behind.

Neal disappeared over the drop. An oar and one side of his raft briefly popped into view a moment later. Christ, he took a hit. I didn’t notice much about the next boat’s line, as I focused on aligning myself right of center, the entry I remembered from the previous summer. As the drop came into view, I saw that our position and trajectory was less than ideal. Below me was a startlingly huge, river-wide wave: crashing foam on the right and left, a towering and intermittently breaking green curler in between. I was already moving toward the center, the meat of the wave. Right or wrong, I made a split-second decision to continue that path. Turning would slow me down, and even if we crashed and burned down there it was a clean swim, in deep water, with no sticky holes that I could see. Time to go big. We came in with as much speed as we could muster, the green wall rising above us, surging at the worst possible moment, breaking over our heads. The boat crashed to a halt and spun sideways. I sensed that familiar rising, listing feeling that usually precedes a flip. Teri tumbled into the foam and I grabbed a boy next to me as he nearly followed. I moved to the high side, thinking we were going over, bodies struggling to hang on. But the raft came down upright. We recovered Teri, who was still close to the boat, scrambled back into position and commenced to celebrate our sketchy but successful run, hooting and hollering and raising our paddles in a high-five salute. One of the kids, distracted, stared downstream. He said, matter-of-factly, “Hey, look.”

I turned and saw a body lying supine across the front deck of Neal’s boat, legs draped over the side. The cockpit was empty, both oars unmanned and dragging in the water. Neal hunched over the body. Shit.

We paddled hard to catch up. A look of dread spread over Teri, barely recovered from her swim. She knew. I knew. Steve had swum Cramer, too.

It was floating mayhem as we tangled with a group of private rafters trying to help out. Neal jumped back on the oars and pulled toward the right bank, wisely landing about a hundred meters or so upstream of the boat ramp. The ramp itself was jammed with rafts, vehicles and what looked like a hundred people. I eddied out just below Neal and scrambled onto his boat.

My first thought when I saw Steve was that he was dead.

He was cyanotic, skin blue and gray, and his eyes bloodshot, yellow and vacant. Neal said he had an airway and very labored breathing. I took his pulse — weak and thready — and found him totally unresponsive. But his color slowly improved with each croaky breath. It was cool and cloudy out, so we quickly gathered a sleeping bag and fleece to warm him up. I located the satellite phone, dialed an emergency number and handed it to Neal, who moved into to his designated trip-leader role as emergency coordinator.

Brandon and I worked to warm up Steve while Arnie shouted in his buddy’s ear. “C’mon, Steve, breathe, you can do it. You beat cancer! This is nothing! We’re pulling for you, come on!” Steve’s wife Mary, sat on the front of the raft, sad, calm, resigned. She shook her head grimly. She was giving up. In the background, I could hear Teri in the paddleboat, crying. Jean was trying to reassure her sister. “It’s okay, they’re doing everything they can.”

Minutes passed as Neal contacted Life Flight and the Salmon ER. One of the other guides sent a guest down the road to the ramp to ask if a doctor was present. Amazingly, he returned with a young female physician who’d been a guest on my friend Jane’s trip, now de-rigging at the ramp. The doctor checked out the patient and came up with the same assessment: hanging on by a thread. She called up to Neal. “What’s Life Flight saying?”

Neal appeared composed and clinical behind his sunglasses. He was on the clock doing his leadership bit now, but I knew the emotions, the self-doubt, the what-ifs, would hit him later. “Fifty-five minutes,” he replied flatly.

The doctor stared me dead in the eye, pursed her lips and slightly moved her head to the side. Way too long. I readied a face shield and timidly suggested we consider assisted breathing, a suggestion that quickly became moot. Steve convulsed and vomited water and sputum. We log rolled him to one side and let him drain, but within seconds his grayish hue turned blue once again. I took a distal pulse as the doctor tried his carotid.

“I got nothing,” I told her.

“No pulse. CPR, let’s go.”

She pulled back the sleeping bag and Steve’s shirt, revealing evidence of the battle he’d fought for three years: his torso was completely perforated with surgical scars. Grabbing a face shield, I tilted his head, pinched his nostrils and put my lips to that thin sheet of plastic, staring into blank eyes as I exhaled. It took a couple of tries, adjusting his head and flattening the mask, but air went in and his chest rose — though something wasn’t quite right. He had to have more lung capacity than that.

The next hour was surreal: breathing, compressions, my lips bruised and bleeding from pressing too hard on Steve’s mouth, the voices around us, more news of delay from EMS. All the while, Arnie never let up his vigil, never stopped voicing encouragement to his best friend. Frank took over breathing after about 10 minutes, but the doctor, on a mission, continued compressions. Almost dizzy, I sat back and tried to comprehend what was happening.

And Billy came to me.

Five years before, I’d been kayaking with a friend named Bill Danford on a class IV-V section of Idaho’s Teton River Canyon. Things went really bad, really quickly, when Billy broached his kayak across two rocks mid-stream. Though I was able to get to him, I failed to free him from his boat. He literally drowned in my arms. The event shattered me. I have lived with the guilt of failure and the guilt of survival ever since, only recently coming to terms with that day.

In the aftermath of Billy’s death, I repeatedly told friends I imagined the only thing worse would be losing a commercial client, someone who put their entire trust and faith in us to ensure their safety. I said if I ever lost a guest, I was done, I wouldn’t be able to guide, or even to boat at all. Prior to Billy’s death, I’d witnessed two Colorado river fatalities, suffered by other river parties, one of which was a commercial trip. And now it was happening to us. We were losing one.

So, is this how two decades of floating and fun and friends comes to an end?

I looked around, catching my breath. Neal was performing flawlessly as a leader, while Brandon and Frank worked with the doctor on Steve. The other guides were efficiently directing and caring for the other guests, who continued to look upon us with trust and faith — despite the fact that we were losing the battle. It’s difficult to articulate, but I could feel their support, not just for Steve and his family, but also for us. They knew we were trained and competent and there for them — and that we were hurting. But they were there for us, too.

Okay. Win or lose, I’m right where I’m supposed to be. It sounds hopelessly corny, a cliché, but the situation made me want to be a better guide, a better person. Fuck quitting.

I rowed the boat down to the ramp as a local first responder vehicle approached, twenty minutes or so since our first emergency call. They beat Life Flight to the scene, but the nearest hospital was a two-hour drive away. I relieved Frank on breathing duty, though I knew at this point we were just going through the motions. As we continued CPR, the first responders set up an AED, a compact defibrillator, but Steve had nothing to give. The electronic voice of the AED indifferently bleated “no shock advised” after each analysis. He was gone.

We kept going for another half hour, mostly for the benefit of the family, Arnie, the crowd around us and for our own collective conscience. I looked up at one point and saw Jane, quietly packing her trip. Our eyes connected and she gave a serious nod. She was with me throughout, and I could read her mind: that could be me, breathing into one of my own guests.

Nearly an hour into the rescue effort, docs at the Salmon ER finally gave us the okay to call it. I felt momentary relief, but immediately began dreading my next duty, or what felt like my duty. I paced around the rescue vehicle a couple of times, trying to hold back tears, trying not to look at the raft on the ramp, a dead man lying on it, staring at a gray sky with lifeless eyes. Hold it together. Do what you’ve got to do.

The girls were at a nearby picnic area with the other guests. Teri sat by herself, head in hands. Stunned guests milled around, organizing personal gear, preparing for a long, quiet bus ride. I knelt before Teri as she raised a disbelieving face, eyes streaming with tears. What do you say when words are wholly inadequate?

“I’m so, so sorry.” I hugged her, then took her cheeks in my hands. “But now you’ve got to be strong, okay? Your mom and sister are going to need you, too.” Sure it was trite, but so true. As an adult orphan who’s been there with my own siblings, I knew this first hand. There’s strength in numbers, especially family. Hell, maybe that’s why this was different than the last time for me. I was with my family. River family.

Teri nodded, managing a weak smile. Her braces were beautiful.

Jean caught my eyes and came to share an embrace. “You guys were awesome,” she said. “I’m so sorry you had to deal with this.” I was dismayed that she was “apologizing” to us. She didn’t know it, but those few words were tender mercies, probably saving us years of guilt. Before my eyes a lovely, college-aged girl became a woman: strong, intuitive, compassionate. Personal qualities I’d taken for granted in another young woman I’d met on the river years before. A woman I’d recently lost.

Mary, the girls and Steve’s friends gathered around his body as he lay on the raft, strangely parked on a concrete boat ramp like a funeral pyre ready to be floated and set alight. Arnie broke down, finally surrendering, sobbing over his friend. I should have told him that when I go, I hope a buddy like him is by my side. The girls cried as well, but Mary appeared stoic throughout, perhaps finally facing a future she’d long known would come.

Yes, Steve had cancer, and yeah, he died. But watching his loved ones around him, saying their good-byes, I wondered if I’d ever be so lucky.

August 3, 2005

Moose Lake, Jedediah Smith Wilderness, Teton Range, Wyoming

I pack away the GPS and check my watch: 4:30 p.m. I’m done logging data for the day, but I’m still looking at a 10-mile hike back to the trailhead. Before me, Moose Lake is a translucent spectrum of blues surrounded by wildflowers and alpine meadow: bright yellows, blues, reds and greens fluttering in the wind like a field of prayer flags, their mantras heaven-bound. I inhale deeply and feel rarefied alpine air massaging my skin. Despite the fatigue from a long day of mountain walking and the prospect of the hike ahead, I’m feeling very much alive and healthy. I’m at my other seasonal job, with the Forest Service, mapping trail conditions in the Teton high country — an ideal place to reflect on an eventful, intense summer.

I guided three more six-day river trips in the Salmon River country after we lost Steve, twice as trip leader. “Everything can go wrong this week,” I told my first crew, “and this will still be the best trip of the season.” Sometimes I’m overly obsessed with details when I’m head guide, but after this June, maybe I’ll learn not to sweat the minutiae. Hell, all three of those trips were the best trip of the season.

And perhaps the first one wasn’t as bad as it felt at the time. Steve spent his final days with friends and family on the Middle Fork — rather than in bed, attached to a morphine drip, the way my mother went out. I know that’s little consolation for a wife and two young women who watched him fade away, but perhaps they’ll see it that way some day. People always said that about Billy, that “he died doing what he loved.” Until recently, I said that was bullshit. I couldn’t get past the memory of his suffering, of his frantic struggle to get his head above water, to breathe, to simply stay alive. But taking the long view, it’s starting to make sense.

I confess that the traumas of my past have left me with a steamer trunk full of baggage: bitterness, anger, resentment and a fear of further loss. This baggage has cost me dearly, even in the best of the times, leading to self-alienation and helping sink my last relationship. I was so afraid of losing her — of reliving the cycle of pain and grief —that my fear became a self-fulfilling prophecy. I withheld my soul, and lost a big piece of it as a result. Watching Steve’s family and Arnie in their finest hour provided invaluable perspective: they gave each other 100 percent of their love, though Steve’s days were undoubtedly numbered. Hell, none of us gets out of here alive, so why be half-assed about it? Life’s too short to be guarded, to hang out in your comfort zone waiting to die a “dignified,” peaceful death in your sleep. Sure, Steve could have sat on the couch and lived awhile longer, but he chose to take a chance and share a special, somewhat risky place with his family. It went wrong, but they lived life for real, together, all the way to the end.

Steve’s passing gave me the push I needed to follow some long-time aspirations of my own: this winter I hope to volunteer with a malaria prevention program in Uganda, while kayaking some big water on the Nile — with Jane, of course. I’m also planning to make my way to Cape Town, South Africa, where I’ll train for my childhood dream of blue-water sailing, work on my skipper’s certification and maybe join a yacht delivery crew headed back across the Atlantic. With any luck, I’ll be home for the summer, guiding on the Middle Fork once again. Yeah, fuck quitting.

Am I expecting a cathartic journey that will make it all better, mend a broken heart and answer the big questions? Oh, hell no. But time, especially time on the water, is bound to heal some (better than liquor, anyway), and maybe spark a little passion. Who knows where it will lead next, who I’ll meet, how it may alter the course of my life?

Most of us too often forget to celebrate love and life, the only gifts we’re given that really matter, until we witness death first-hand. It is a visceral, dreadful, final reminder of how fleeting and precious our existence really is. How many times must we be reminded before we finally heed the lesson?

Author’s note: This piece was adapted from an email I sent to friends and family in the summer of 2005. I did indeed travel to Africa during the winter of ’05-’06, following the very itinerary I imagined — including a sailing voyage across the Atlantic. I currently live in Steamboat Springs, with a wonderful lady and her daughter, and continue to guide part-time on Idaho’s rivers.

A refugee from Los Angeles, Rob Marin has performed a wide variety low-paying jobs on the Pro Leisure Tour, from dishwashing and journalism to ski patrolling and sailboat delivery. He currently teaches geography and mapping technologies in Steamboat Springs, Colorado.