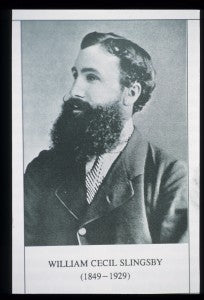

Step back to the Golden Age of English mountaineering when William Cecil Slingsby pioneered routes in Norway, including Storen, which was believed to be impossible to climb at the time. By M. Michael Brady

The golden age of mountaineering among English-speaking peoples arguably started in 1857 with the foundation of the first Alpine club in London, described as: “a club of English gentlemen devoted to mountaineering, first of all in the Alps, members of which have successfully addressed themselves to attempts of the kind on loftier mountains.” (The Nuttall Encyclopaedia 1907).

It was the Victorian Era, in which Englishmen of means and wanderlust explored countries abroad and upon returning published travelogues of their adventures. One of them was Edward Whymper (1840-1911), the English mountaineer who led the first ascent of the Matterhorn in 1865 and included an account of it in Scrambles Amongst the Alps in the Years 1860-69 published in 1871 in London. (The book has since been republished several times, most recently in 2002 by National Geographic Books.)

News of Whymper’s exploits drew many to mountaineering, including a young Yorkshireman, William Cecil Slingsby (1849-1929), then a teenager with a penchant for hiking and outdoor life. He was the oldest of six children, born into the Slingsby family that owned and operated the Carleton Mill, built in 1861 for spinning cotton.

At age 23 in 1872, Slingsby embarked upon his first expedition to Norway, in which he made a circuit of the central mountain cordillera. In the Hurrungane Range of the Jotunheimen Mountains, he caught sight of Storen, also known as Store Skagastølstind (“Big Skagastøl Peak”), then said to be unclimbable. He took the peak’s reputation as a challenge; he would be the first to climb Storen.

The mountaineering challenge of Storen was quite like that of the Matterhorn that had faced Whymper. Both peaks are massive pyramids with similar prominences (minimum vertical climb from col), 3,310 feet for Storen compared to a bit more, 3419 feet for the Matterhorn. Both peaks are the only ones in their massifs that on all approaches require what now is called technical climbing. Only their summit elevations differ: 7,890 feet for Storen, compared to 14,692 feet for the Matterhorn. The 6,802-foot difference in summit elevation reflects a topographical dissimilarity: The mountain chains of Norway rise from sea level, while those of the Alps rise from high continental strata. Save for acclimatization to higher elevations, climbing in Norway can be as challenging as climbing in the Alps.

In 1874, Slingsby returned to Norway, with a crammed itinerary of climbs including one first ascent. Upon returning from the mountains via coastal steamer, he met educator Emanuel Mohn (1842-1891), known for his writings on and illustrations of mountains. The two men found that they had much in common, particularly their quests for first ascents.

In 1875, Slingby returned again, to the Jotunheimen range, with his sister Edith, who became the first woman to climb Glittertind, Norway’s second loftiest peak with a summit elevation of 8,087 feet. At Mohn’s suggestion, he described her experience in an article, “An English Lady in the Jotunheimen”, published in The Norwegian Trekking Association’s yearbook that year. In the winter of 1875-76, Slingsby and Mohn wrote each other to plan a major climbing effort the following summer.

In July 1876, Slingsby and Mohn met in Oslo and traveled by carriage to Bygdin Lake in the Jotunheimen Range where they met up with Kunt Lykken (1831-1891), a local farmer, reindeer herder, and mountain guide. The three then spent five days making five first ascents, a record that still stands in Norwegian mountaineering. On July 21, they set out to be the first to climb Soren. The weather was foul, but they were successful, with Slingsby climbing the final stretch to the summit solo, as he was more skilled in rock climbing than Mohn or Lykken.

Thereafter, Slingsby returned to the Jotunheimen five times. In 1888 and 1899, he climbed in Northern Norway. In 1900 he again climbed Storen, and in 1903-1912 he again climbed in Northern Norway. In all, he is credited with 50 first ascents, the last in 1912. His zeal for climbing in Norway was matched by his ability to get along in the country. As a Yorkshireman, he felt a common bond with Norway that stretched centuries back to the days when Vikings raided eastern English shores. In the course of his many visits, he became fluent in Landsmål, the language of the rural districts he frequented; now called Nynorsk, it’s one of the two official languages of the country.

In 1921 he visited Norway twice. On the second visit, his last in Norway, he was accompanied by his daughter Eleanor, an enthusiastic climber who had founded the predecessor of the Pinnacle Club, a women’s climbing association in the UK. That year in Oslo, King Haakon 7 granted Slingsby an audience.

In addition to his climbing accomplishments, Slingsby documented what he did, in more than 30 articles in the Alpine Journal, the Norwegian Trekking Association Yearbooks, the Climber’s Club Journal and the Norwegian Club Yearbooks. His book, Norway, the Northern Playground, was first published in 1904 in Edinburgh and since has been republished several times, most recently in 2010 by Nabu Press of Charleston, South Carolina.

After his last climbs in Norway, Slingsby continued climbing in the UK, and when well into his 70s, was climbing on Gimmer Crag and Pillar Rock in the English Lake District, known for its challenging rock climbs. Sports were his life, to its end. On his deathbed at age 81, he looked out through a window to see boys playing cricket outside. A boy at bat swung well and sent the ball for a six (in cricket, the equivalent of a home run with the bases loaded in baseball). “Well played, well played, my boy!” he cheered. Those six words were his last.

After his death, The Times of London observed in his obituary that “For a mountaineer and explorer, he had the ideal equipment—a magnificent physique, exceptional hardihood, grace and agility, an unerring judgment, coolness and courage.”

In his native England, he is remembered along with other Slingsbys of history, geography, literature, and business. There’s a Slingsby Day, commemorating the execution in 1658 of Yorkshire landowner Sir Henry Slingsby for his adherence to the Royalist cause during the English Civil War (1642-1651). In North Yorkshire, there’s a small village named Slingsby. American-born, British naturalized poet TS Elliott (1888-1965) wrote a poem about Miss Helen Slingsby. English naval administrator Samuel Pepys (1633-1703) mentions a Slingsby in his famed diaries. Today, Slingsby Aviation makes hovercraft, two of which appeared in Die Another Day, a James Bond movie released in 2002.

In Norway, Slingsby is regarded to be the father of Norwegian mountaineering. Two topographic features bear his name: Slingsby Glacier, below Storen, and Slingsby Peak in the Jotunheimen, formerly Nordre Urdanostind (“North Urdanos Peak”), of which he made the first ascent on July 10, 1876. The Norsk Fjellmuseum (“Norwegian Mountain Museum”) in the village of Lom, just north of the Jotunheim Mountain range has a modest collection of Slingsby memorabilia, including many of his diaries, notebooks, sketchbooks, paintings and articles on climbing in the Alps and in Norway.