By Hannah Truby

The Squatch Bus

Remote. Rough roads. No cell service. Even for Canadians, the Yukon can be a daunting place to travel. To the rest of the world, it can seem like something of a secret. Reaching its capital, Whitehorse, took me three planes and a taxi—and even then, I was only at the territory’s gateway. Traveling to such an isolated place always entails some adventure–but isn’t that the point?

“I’ve always wanted to go, but it's not exactly the kind of place you can just pick up and check out on your own,” Ethan said when it was his turn to explain why he had booked the trip.

We’re currently on the Yusquatch Adventures bus. It’s a retired school bus—obvious from its exterior—but inside, it’s a fully outfitted rolling basecamp: six bunks, a bookshelf, a kitchenette with sink, stove, and fridge, one toilet, and an array of solar panels on the roof.

It’s scrappy, and it works. A true labor of passion.

Ethan is an Irish ski bum working at Whistler on a work travel visa. Sitting across from us are Florentina, a digital nomad from Germany, and Larese, a freshly retired Calgarian. We’re total strangers, and could possibly have nothing in common other than the fact that we’ve all willingly signed up to spend a week sleeping in a school bus and hiking deep in Yukon territory.

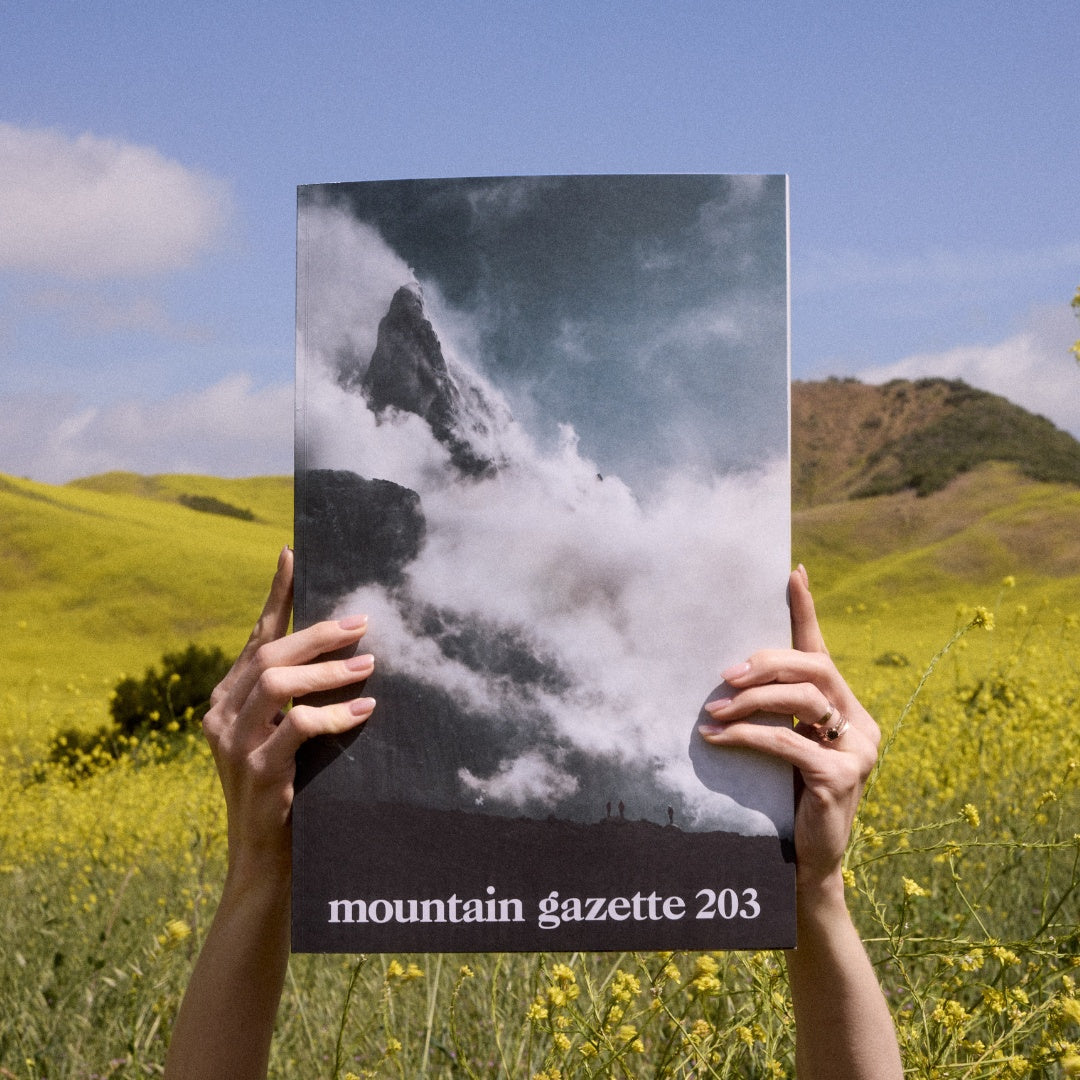

Even on paved roads, the ride is bumpy and loud. Tin cups and alcohol bottles rattle and clink as the bus makes its way out of Whitehorse–a sound which would become a strangely comforting playlist to accompany the days ahead.Among the group, I am the only one here for “work”, which draws surprise—and, of course, a little envy—when I tell them. Mountain Gazette had been invited by Explore Canada and Parks Canada on a dual-destination media trip designed to show journalists a side of the country that tourists rarely see–and Raph tells me there's no more perfect place than the Yukon.

Raph and Stephanie are the duo that make up Yusquatch Adventures. With the Squatch Bus as their base, they take clients on multi-day, multi-sport adventures in the mountains, giving small groups the chance to experience vanlife in the Yukon–and vanlife is something Raph knows well.

After six years in the military, he bought a van, left his home of Quebec, and headed west with only the goal of exploring Canada’s most remote corners. He knew he had found what he was looking for when he reached the Yukon.It was everything he thought adventure should be, he later told me—raw, remote, real. He created Yusquatch so others could experience it, too—really experience it, not just through guided hikes or gear lists.In truth, I didn’t share my fellow bunkees’ long-held aspirations of visiting the Yukon—mostly because I didn’t know what awaited me. Which, of course, made it the perfect place to start.

Into the Yukon

My trip to Canada’s most northwestern corner marked only my second time in the country—the first had been a brief three-day visit to Vancouver—so I spent the days leading up to the trip researching as much as I could. It quickly became clear I was in for something special.

Some quick facts about the Yukon:

- There are twice as many moose as people. With a population of 34,157, the Yukon is one of the most sparsely populated places in Canada. On its highways, seeing no more than a single vehicle over countless miles is more rule than exception.

- It's insanely huge. As big as Spain, the territory is made up of miles and miles of boreal forest, mountains, and hundreds of thousands of lakes.

- Much of the Yukon’s appeal lies in its rugged wilderness, rich Gold Rush history, vibrant Indigenous culture, and northerly natural phenomena like the Northern Lights. Many consider it to be one of the last truly “wild” places left.

As we drive along the Alaska Highway (once called "the biggest and hardest job since the Panama Canal"), and the Yukon of my imagination—remote, wild, almost mythic—unfolds before us.

En route to our first night’s campsite, we make a stop at the Da Kų Cultural Centre in Haines Junction. Da Kų is a Southern Tutchone phrase used by Yukon First Nations meaning “our house.” It’s as much a visitor center for the park as it is a cultural hub for the Champagne and Aishihik First Nations people.

For many Indigenous people, Canada’s national parks are synonymous with colonization. Built on the idea of protecting ‘untouched’ wilderness—a notion rooted in racist legal fictions like the doctrine of discovery and terra nullius—the establishment of the parks was premised on Canada’s assertion of control over First Nations' land and resources. In practice, creating these parks often meant removing communities from their homelands and criminalizing their traditions such as hunting and fishing in the name of conservation.

Over the last several years, Parks Canada has been working with First Nations to reshape that relationship, and have been working to expand Indigenous Guardian programs—local stewardship jobs that put “moccasins and mukluks on the ground”, such as the Champagne Elder we meet at Da Kų.

"Look at your feet!" she tells us. "If you look closely, you’ll notice the highways were built following the footsteps of my ancestors. We’ve always known where to go, long before the roads came.”

King’s Throne

As we set out for our hike the next day, I imagine following in the First Nations’ footsteps, appearing and vanishing across the land in wisps of smoke like on Harry Potter’s Marauder’s Map.

King’s Throne is the biggie of our hiking adventures—a trail that feels less like a hike and more like an initiation—but an absolutely worthwhile one, nonetheless.

As we start for the treeline, Raph gives us the stats: 15 kilometers, 1,250 meters of gain, eight hours, “very difficult”. Never wanting us to push beyond our limits, our guides always give us the option to turn back on any excursion. I, of course, couldn’t imagine doing that, not when I work for a magazine whose motto is "When in doubt, go higher."

Out of the treeline, the trail swoops upwards and transforms into a rocky and incredibly steep series of switchbacks that ribbons up the rock glacier before us.

Four miles in, we hit a plateau: an amphitheater of rocky ridges, the ‘seat’ of King’s Throne and our perfect lunch spot.

The next climb is steep—really steep. The trail quickly blurs into a scramble of loose gravel and we seem to have entered a completely different weather zone. Gusts of wind slap at us as we reach the top of the ridgeline. They’re strong enough to shove us sideways, and I accept Raph’s offer of a hiking pole.

We lean into the wind, inching along the knife-edge until the final rise gives way to the summit. And then:

An endless sweep of icefields and mountains, valleys, and rivers stretching seemingly without end. The day was clear, and we could see the large massif of Mount Alverstone, as well as Hubbard, Kennedy, and other peaks straddling the Alaska border. It was one of the most insane views I had ever earned—the kind that reminded me how small I was and how infinite the land could feel.

Stories by the Fire

Growing from the shores of Kluane Lake in all directions is Asì Keyi, (My Grandfather’s Country) a boreal forest nation, stretching to the Ruby and Nisling mountain ranges to the northeast and the St. Elias Mountains to the southwest. We spend each night in a new location—every one of them beautiful—but here, on the shores of Kluane Lake at sunset, tonight’s views are especially spectacular.

Raph inflates the paddleboard and kayak, and with what remains of daylight, I glide across the impossibly huge lake.

Ethan and I are on dinner duty tonight, which for us means throwing a concoction of ingredients together into a big pot on the tiny stove top, stirring and tasting and adding salt until we are content with calling it “stir fry”. The others get to work outside, propping up the chairs and setting the table with plates and wine while Raph gets started on the fire.

Tonight, we are joined by Pauly Sias, a local Kluane First Nation (KFN) Heritage Manager, and her wolf dog, Willow. As Heritage Manager, Pauly is responsible for the stewardship, preservation, and interpretation of her nation’s cultural heritage—including traditions, languages, artifacts, and cultural sites.

Pauly tells us that, for First Nations, the most important way of passing down knowledge is through story. So, as the day fades to night, we gather around the fire, sip wine, and marvel at the many she has to share. We exchange questions, too, and pass around treasures she's pulled from her bag—a skinning knife made from moose shin, a ladle carved from antler, old family photos—and with each, a new story unfolds.

This night stands out as a favorite from the trip, a reminder that the privilege of being here wasn’t just access to wilderness—it was being welcomed into a new land, with stories older and far more complex than my own.

If the Yukon showed me Canada in its rawest, wildest form, Alberta promised a different kind of immersion—a little more curated, but just as rich, with fewer mountains and more buffalo.

In two weeks: The journey continues with Part 2 of Hannah’s Canada Chronicles. Stay tuned.