This piece was originally published on MountainGazette.com in 2012. We're republishing it here for readers of our Sunday email.

By John Fayhee

Several years ago, I was given an assignment by a glossy outdoor magazine to pen a story about hiking Peru’s famed Inca Trail.

First view of Machu Picchu before sunrise from Intipunku. By Colegota Author’s note: Several years ago, I was given an assignment by a glossy outdoor magazine to pen a story about hiking Peru’s famed Inca Trail. After I completed the hike, but before the article appeared in print, there was an editorial coup d’état at the magazine and my Inca Trail piece was a casualty. I have long wanted to nudge the story into print and decided — what the hell? — now’s as good a time as any. Please note that, even though this installation of Smoke Signals is longer than usual, this is still a truncated version of what turned out to be a very long example of Fayhee bullshit.

For my entire adult life, I had fantasized about this, the moment I was about to embark upon the train ride that would take me to and deposit me at Kilometer 88, a skanky trackside cluster of partially assembled, partially disassembled, dusty shacks so dismal it deserves a pedestrian name like K-88, which marks the beginning of Peru’s 55-mile Inca Trail. I had wanted to hike the Inca Trail for so long that I can’t remember when or why that particular dream began. Its lack of palpable paternity aside, the dream consisted of many rational components: Trekking along an arduous route through the heart of the Andes. World-class mountain scenery combined with the colorful Quechua Indian culture. A cobbled pathway that pre-dates Columbus’ voyages to the “New” World. And, most importantly, Machu Picchu, the famed “lost” (and found) city of the Incas uncovered (if not actually discovered — a little etymological two-step, there) by the American archeologist Hiram Bingham in 1911.

For many years, political circumstances (read: the Sendero Luminoso unpleasantness, which often specifically targeted tourists) convinced my wife Gay and me to give Peru a wide berth (call me a pussy). Things have changed enough in the past few years (though they are slowly changing back, from what I hear) that we finally decided to pack our packs and make the long-anticipated journey to the heart of Inca-land.

The train to Kilometer 88 huffs and puffs and wheezes its way up several switchbacks as it climbs up the mountainside out of the absolutely chaotic station in Cuzco, a city of 300,000 that is located at almost 12,000 feet. After it crests out, we begin our descent into the Sacred Valley of the Rio Urubamba, which we will follow all the way to the trailhead.

It’s wonderful, though stark, countryside, more arid than alpine, despite the elevation and despite the fact that we are only 16 degrees south of the Equator and less than 100 miles west of the decidedly un-arid and un-stark Amazon Basin. The kilometer signs slowly tick by as we make our way through small towns I’ve been reading about for decades: Izcuchaca, Zurite, Ollantaytambo, the lyrical names flowing into the each other like the swift water of the river we are following. (Translated, those lovely names probably mean things like “Snarling, Rabid Dog-ville” and “Place Where All the Seething Displaced Senderos Now Reside.”)

Halfway between Cuzco and Kilometer 88, the snow-covered peaks of the high Andes begin to appear in the distance. It is both sobering and frightening to realize the mountains we are now eyeballing are almost 9,000 feet higher than the loftiest peaks of Colorado.

We stop briefly at Kilometer 82, an alternative starting point for the Inca Trail. A few members on the teeming backpacker masses with whom we are sharing the train shoulder their packs and get off. And when I say “masses,” I am not being hyperbolic. Back at the train station, I considered it a physical impossibility that everyone there gathered would be able to fit upon one archaic train, and, if they did manage to squeeze onto those faded cars, I doubted very much that the antiquated locomotive would be able to successfully pull us to our intended destination. Yet, fit they did, as long as you have a loose definition of “fit.” Every available square inch is occupied by gringos from all over the world. Many of our fellow pack-toters, like us, have come to Peru specifically to hike the Inca Trail. And many others are on extended “Lonely-Planet”-type trips across the known universe.

The crowded train comes as no surprise; we knew before coming to Cuzco that we would be on the scene during the apex of the tourist season: mid-winter (south of the Equator), when the days are cool and the skies are generally clear. (We talked to one Brit who had hiked the Inca Trail a few years prior in during the rainy season. He told us he was pretty much the only person on the trail at that time, but, solitude aside, it was a miserable journey insofar as it did not stop raining the entire time, an experience necessitating a return journey during the dry, though populated, season.)

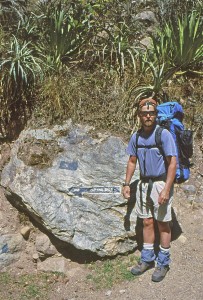

Fifteen minutes later, we’re there: Kilometer 88, one of the most-famous trailheads on the planet. Much to our delight, “only” about 200 other hikers disembark. The rest of the tourist hordes stay on the train, which goes all the way to the town of Aguas Calientes, at the base of Machu Picchu. (I should note here that you are only allowed to hike the Inca Trail in one direction — toward Machu Picchu.) Gay and I dilly-dally on the side of the tracks, re-organizing our packs and preparing for a hike that, though famous and well-trod, is, by all accounts, pretty damned difficult.

When we’ve got our ducks in a huddle, we walk down toward the trailhead. Much to our dismay, we see before us a line of hikers 50 yards long. Since the Inca Trail is part of the massive Machu Picchu Cultural Park, and since this is also the heart of the bureaucracy-crazed Third World, we learn there is much in the way of paperwork to be filled out and much in the way of money to be handed over. It takes more than an hour to buy our entry permits and fill out the requisite forms, which are stamped and handed back to us by a couple of no-nonsense-looking (and well-armed) gendarmes whose demeanor can best be described as desultory, like, shit, I joined the Peruvian Army to see the world and/or to kill or be killed by Sendero rebels, and here I am issuing hiking permits to backpack-bedecked gringos and Eurotrash.

The trail starts out at 7,500 feet — 1,600 feet lower than we lived at the time — following the Rio Urubamba through a wonderfully shady eucalyptus grove. It’s very easy going at first, and we are both beaming. After all these years of planning and, more importantly, dreaming, I am finally beating feet upon the Inca Trail.

Our orientational arsenal consists of one pleasantly outdated guidebook, a mid-’70s edition of Hilary Bradt’s “Peru and Bolivia: Backpacking and Trekking” that I horked from a youth hostel in British Columbia in 1980. I generally eschew guidebooks (verily, I hate the goddamned things, being of the firm belief that the world was a far more interesting place before it was guidebooked into a catatonic stupor by writers trying to figure out a way to make a living from traveling, aided and abetted by readers who apparently are not comfortable with the concept of surprise), but, since this one was venerable and tattered enough that it could be best described as a work of torn-page historic fiction, I opted to carry it with me despite my anti-guidebook prejudice. I also had one non-topographic map that looked more like a placemat you’d find at Denny’s than it did a useful trail tool. It was, however, the best we could find in Cuzco, though, as we were unable to locate any “real” maps of the area.

It becomes obvious from the get-go that we will need neither a map nor a guidebook to stay on the trail. This is tread that has been used as a fundamental transportation artery for so many millennia by so many uncountable gabillions of people that you could near-bouts navigate it drunk with your eyes closed in the dark, even if you do not have as much experience as I do navigating trails drunk with your eyes closed in the dark. At this point, the trail is actually just that: a trail — good ol’ dirt and rock — rather than the Inca-crafted stonework “highway” we will walk upon for the last two-thirds of the hike.

It is almost 1 p.m. before we leave the river bottom and begin our first ascent, into the valley of the Rio Cusichaca. Though it is hot, I press Gay — who only enjoys backpacking if she can do so at a pace that borders on — how to say this tactfully? — deliberate — to push on without a break. As much as I am trying to deal non-negatively with the numbers of people on the trail, truth be known, I am worried about getting a campsite. That’s a relevant little gem that our guidebook has laid on us, a gem that had remained germane ever since the tattered tome was published more than 20 years prior: In a land with this much severely vertical terrain, level turf is a rarity. There are only a handful of decent camping areas on the entire trail, and many of them are taken early in the day by employees of the various tour companies.

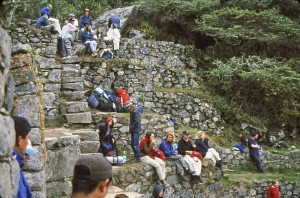

The overwhelming majority of the people who hike the Inca Trail sign on with these companies, which employ local Quechua Indians to do the dirty work, such as carrying everyone’s packs, running ahead to lay claim to entire valleys and having tea and crumpets prepared when the customers arrive. (I should note here that, since Gay and I hiked the Inca Trail, laws have been enacted making the use of guiding services and guides mandatory.)

It’s not like we did not have the opportunity to sign on with a guided tour company. You can’t swing a dead cat in downtown Cuzco without hitting someone who’s trying mightily to sell you an all-inclusive, deluxe, guided, provisioned, portered journey along the Inca Trail. Verily, pretty much as soon as you step foot in the city’s Plaza Mayor, urchins associated with the various guiding companies will pretty much latch onto your leg like an irate wolverine and hold on until you agree to their terms or kill them, whichever comes first. And the cost is certainly not prohibitive, anywhere from $50 per person per day to $200, depending on quality of food, gear and guides.

Much to the chagrin of my wife, I have never liked the idea of being guided along a trail, especially one as obvious as this, and I certainly can’t abide the notion of having someone else carrying my pack. It’s cheating, and my old-school purist glands can’t handle it. Many people argue that, by hiring guides and porters, you are mitigating your visitation impact by putting money directly into the local economy. That’s a perfectly valid perception, but just one that I personally prefer not to buy into for selfish reasons that might karmically catch up with me at some point, like when my aching right Achilles tendon finally gives out for good.

Temptation along the Inca Trail does not just take the form of the pre-paid, pre-arranged guided tour companies. For the first day and a half, we pass dozens of freelance porters, locals who sit alongside the trail, offering to carry the packs of any gringos whose tongues are clearly dragging in the dust. Since these sturdy men only charge a few bucks a day, it’s not long before Gay is seriously considering making the freelance porter leap, with or without spousal buy-in. I am married to a woman who loves hiking and camping about as much as a person can. But she viscerally hates carrying a full pack, and she can’t, for the life of her, understand why she married a fool so stupid/egotistical/stupid that he won’t consider even for a moment giving in to good sense when opportunity knocks as loudly and as inexpensively as it does with these trailside freelance porters, all of whom flex their quads and smirk as we approach.

Just before the village of Huayllabamba, we pass the first decent-looking campsite, right on the banks of the Cusichaca. Good thing it’s too early to even contemplate parking it for the night, as it has been completely commandeered by a tour company that, judging from the scale of the operation, seems to have the entire population of Germany as its clientele. Rows and rows of identical tents are set up side-by-side, making it look like a massive 19th-century cavalry encampment. Though we have been assured that these companies have no legal right to dibbs entire camping areas, the fact that they get there first and take up every available inch of level land means they, de facto, do dibbs these areas. My concern for finding a satisfactory place to pitch my tent this evening grows.

Within the modest city limits of Huayllabamba, we pass two more guided-tour-dominated camping areas, each with surly looking Quechua men scowling at any passersby who so much as cast a fleeting glance at “their” heavily tented domains. Several customers are in the camps, sitting in cushy lawn chairs and sipping refreshing beverages. They cast furtive glances at those of us humping our way up the steep hill under the burden of full packs. But they don’t glance long, before returning to their conversations about, I’m sure, this season’s most intriguing interior tent-decorating schemes.

Real backpackers carry their own stuff, I tell Gay, and they are the only ones who have any right to say they’ve “hiked” the Inca Trail. Gay glances over at the reposed, comfortable beverage-sippers and sighs.

We are now following the lovely little Rio Llulluchapampa through a tight canyon. The hiking wheat is beginning to get separated from the hiking chaff, as one-by-one, our trail brethren begin to get hit head-on by the double whammy of altitude combined with the severity of the terrain. Gay and I find ourselves passing just about every person we saw in line back at the trailhead, and we don’t even feel as though we’re pushing it too hard. Guess that’s one of the advantages of living for multiple decades at altitude.

We cross the Rio Llulluchapampa on a small footbridge at about 3 p.m. Just past the bridge is a wide-open field with numerous tent-sized flat spots. This close to the Equator, it’s dark by 6, so we run over and lay claim to what ends up being a wonderful and fairly private site. Over the course of the next few hours, a fair number of other hikers straggle in, and we lose any sense of privacy, but we’re still off pretty much by ourselves in a place that boasts the two most important components of camping: astounding vistas and a secluded spot for the wife to piss.

For most of the day, mist has been mixing with fog and clouds off in the distance. Just before dark, all visible atmospheric gas dissipates and we are facing one of the most awesome sights I have ever witnessed. On the other side of the Llulluchapampa Valley, the mountains are eye-popping: Several thousand feet straight up and covered with luxuriant, cliff-hanging vegetation. If that one wall of mountains was the only scenery we saw on the entire trip, we would have reported back to our chums in the Mountain Time Zone that we had witnessed one of the most astounding mountain vistas on the planet. But, as the puffy white clouds parted in the distance, we came to realize that most of what we were seeing were not puffy white clouds at all, but, rather, the snow-covered summits of the Salcantay Range — the highest mountains in the area, which make Elbert and Massive look like some wussy topographic shit you’d see in Connecticut.

Most people take four days and three nights to hike the Inca Trail, though it can certainly be done in three days, and, more importantly, it can be done in five. Or six. No matter how many days you take to hike from Kilometer 88 to Machu Picchu, there is one day that stands by its high lonesome self on a pedestal built atop a base of reverence, awe and dread. That day is called, well, “The Second Day.”

The crux of The Second Day is a pass called Abra Huarmiwañusca, which translates to “Dead Woman’s Pass.” There are three passes on the Inca Trail, each lower than the prior. Dead Woman’s Pass, the highest point on the trail, is a respectable 13,776 feet — higher than I’ve ever carried a full pack in my life. The statistics alone certainly had Gay’s undivided attention. More than that, though, she found the nomenclature captivating.

“Bet the woman who the pass was named after had a husband who wouldn’t hire a porter to carry his poor wife’s pack,” the love of my life stated as we shouldered our loads.

Since the exact nanosecond we got out of the tent, the freelance porters started arriving, assuming that a long night of trail-borne aches and pains being exacerbated by a night of sleeping on the ground would convince a fair number of gringos to utilize their services. And those porters were right, as many of the people we crossed paths with the first day hit the trail pack-less. All seemed a bit embarrassed when that point was raised by my hyper-sensitive self.

The trail immediately shot skyward through one of the most intense sections of cloud forest in the area. Cloud forest — bosque nubladoin Spanish — is one of those biomes that many people lump under the generic heading of “jungle.” It is hyper-dense forest, usually at 6,000 feet or higher, that collects most of its moisture from the air, rather than from the soil. Cloud forest is always thick with bromeliads and vines, and it’s always cool and shady. The cloud forest through which the Inca Trail passes is heavily laden with many species of orchids, making the walk a favorite among flower-o-philes.

It is also home to numerous exotic species of animals, including the Andean (speckled) bear, the puma, the colpeo fox and the pygmy deer. And, for those who pay attention to this sort of minutiae, there are supposed to be a couple species of venomous snakes hereabouts. Though, truth be known, Godzilla could be standing in a patch of cloud forest three inches from your face and you wouldn’t see him; the vegetation is that thick and impenetrable.

Soon we pass out of the bosque nublado and into the sun-scorched open. Far ahead, we could make out Dead Woman’s Pass, still three hours away. It was hot and dry, and scores of red-faced backpackers — mostly of pale, northern European descent —looked like they could, and probably would, pass out at any moment as they made their lead-footed way upward. The freelance porters who had stationed themselves along this section of trail had more business acumen than an entire university full of MBA candidates. Their services at this point were so much in demand that they could pretty much name their price. In addition to negotiating pecuniary remuneration, they were also demanding food, gear and, for all I knew, blowjobs. Weary backpackers were having arguments over who was going to hire which porter.

I felt good, at least partially because, unlike most of my fellow hikers, the altitude was not affecting my long-time mountain-dwelling self. And I’m a good uphill hiker. So I was able muster a modicum of physical dignity when I reached the summit, where the teeming masses were all lying flat on their backs, near death, tongues lolling out of their mouths. My trail brethren could not have been more sprawled out had they been dropped en masse from an airplane passing far overhead. While I stood on the pass, saying things like, “I can’t believe we’re here already,” I got a sobering visit from the little devil that often pops up on my shoulder and whispers prescient shit into my ear when I most deserve it.

“Your time is coming, asshole,” he said. Then the little devil grabbed my head and faced it downhill. I hate long, steep downs, and they hate me. And we were about to embark upon the first of three nasty, quad-killing Inca Trail descents.

Unbelievably beautiful though it was on the pass, it was also very windy. Gay and I dropped down a few hundred feet on the other side and ate lunch behind some huge boulders with a jovial group from England, who, despite the fact that we were only two days out, were already fantasizing out loud about food. “Hey, mate,” one of the Brits said to me, after learning my nationality, “you don’t happen to have any American cheeseburgers with you, do you?”

“No,” I replied, “but I did bring some freeze-dried steak-and-kidney pie.”

“Ah, steak-and-kidney pie … I’d kill for steak-and-kidney pie,” he replied. (Author’s note: Even though I was born in the U.K., and even though most of my family continues to reside there, I disavow any cultural connection to a food item known as “steak-and-kidney pie.”)

Everyone was in good spirits, despite the fact that many people on the Inca Trail were obviously having trouble with the physical part of the hike. Gay and I both noticed that there were good vibes all along the trail, the lack of solitude notwithstanding. Part of that could have been because most of our fellow hikers were from Europe, where crowds in the backcountry are the norm. There was more to it, though: We had all come halfway across the world to experience this experience, and that gave us some significant common ground with each other, a feeling of on-trail camaraderie that you don’t often find along the human-dense footpaths of, say, Rocky Mountain National Park or the Presidential Range, where every other hiker is viewed by most people as a solitude-killing interloper.

The toe-scrunching 2,000-foot, two-mile descent into the Rio Pacamayo Valley took only an hour, but it provided a sign of things to come. By now, more and more of the “trail” consisted of perfectly placed, almost cobblestone-like rocks and steps, all laid together with expert precision by the Incas (or, more accurately, by their slaves) millennia ago. Though the engineering was worthy of all of the intellectual appreciation I could muster, it was not the sort of perambulation venue that my corpus delecti liked. The stone steps determined the length of my stride, and my footfalls were not exactly softened by the granite. Toward the bottom of the valley, I began to wonder if I would be the only Inca Trail hiker in history to hire a freelance porter to carry his pack on the downhills.

The scenery was astounding enough that, every once in a while, I forgot about the fact that my knees and feet were starting to send more and more red alert-type messages to my cerebral cortex. This was bonafide Andean alpine country, with lush meadows, waterfalls and towering rock faces that framed the entire valley.

Grim reality, Inca Trail-style, reared its head at the bottom, though. Every square millimeter of ground that was even remotely level was taken over by the guided tour companies, the employees of which were scurrying around like butlers on speed preparing lunch for their non-pack-carrying customers, all of whom were probably so damned parched that, if they didn’t get a spot of tea within two minutes of their arrival, they’d expire. The guides were running down to the river to fetch water, setting up tables and chairs and hunkering over propane stoves cooking all manner of chow that smelled far better than, as a random example, the energy bars upon which Gay and I planned to dine. We stopped only long enough to fill our water bottles, before heading up to the Second Pass, two miles and 1,000 vertical feet away.

It felt wonderful to be hiking uphill again.

For the first time since we arrived in the Andes, serious, rather than decorative, clouds moved in. The wind kicked up and, with the sun blocked, it was chilly going up the Second Pass, located at an altitude of more than 12,000 feet. Halfway up the pass lay the ruins of Runquraqay, where there are numerous potential campsites. We were early enough that no tour groups were on the scene, but it was cold enough that we opted to move on, but not until we checked the ruins out. Though by Inca Trail standards, it’s fairly small taters, we spent 45 minutes marveling at the intricate engineering, running our fingers along the seamless, mortarless stonework mastered by pre-industrial-revolution native craftsmen.

Then we hump it up to the crest of the Second Pass, where there are a couple of alpine lakes and several primo campsites. Again, the misty-chilled weather chases us down, into the valley of Sayac Marca, the most amazing set of ruins between Kilometer 88 and Machu Picchu.

On the way down, we noticed something startling: We are completely alone. The crowds have finally thinned out. Me and the missus have dusted the masses. We be bad.

Once again, the descent took place primarily on bone-jarring stone steps built well before Christopher Columbus sailed the ocean blue, and, by the time we reached Sayac Marca — which, like Machu Picchu, was “discovered” by Hiram Bingham — our thighs hurt so badly, we were ready to camp right there in the middle of the trail. We pay a short visit to the ruins before walking stiff-legged off to Chaquicocha, a campsite visible from Sayac Marca a half-mile away. Once more, we find a great place to pitch our Clip-3, with views that are ball grabbing in every direction. To the southwest, we can see Sayac Marca, with sheer mountain walls behind the ruins and the glaciated giants of the Andes behind that. To the north and east are waterfalls, and in every direction are cloud-forest-covered cliffs.

Chaquicocha itself has a small building that boasts flush toilets and running water, with a nice pipe spring outside. Like most of the campsites along the Inca Trail, there’s a little more trash than one would ordinarily find in American national parks, but, all told, we’ve been pretty impressed by the cleanliness of the trail, despite its high amount of use.

We get to the 11,742-foot Third Pass just as the sun is rising above the Urubamba Valley, many thousand feet below us and just as the porters working for a guided tour company are in the process of disassembling their massive, Raj-esque camps and packing up. From the looks of things, there were a lot of people here last night, but they have already departed. The porters go about their work with precision and speed borne of uncountable such camp-breakings.

These porters are almost otherworldly with regards to their on-trail abilities. They remind me very much of Mexico’s Tarahumara Indians, a tribe with which I’ve spent a lot of trail time. For the entire hike, we’ve been

passed by long lines of porters carrying 50-kilogram loads on rudimentary wooden packframes. They literally run up and down the trails wearing nothing more than flip-flops or ratty old running shoes. Their legs look more like gnarly tree trunks than human appendages. I do notice that there don’t seem to be many old porters, though. It doesn’t matter who you are, you carry enough weight enough times at a fast rate up and down a rock trail, and your knees are going to eventually give out. (Just ask long-time hutmasters in New Hampshire’s White Mountains, most of whom have nicknames like “Gimpy” and “Shuffles.”)

All for a couple bucks a day. And my guess is workman’s comp is not real big here.

Just before we begin the last — and by far the longest (5,000-plus vertical feet) — descent of the hike, I find myself standing next to a group of Dutch people who are part of a guided tour. They are having some pertinent skinny laid on them by their Peruvian guide, who’s orienting them to the surrounding territory. If there is one reason I would choose to hire a guide, it would be this: The constant barrage of information and interpretation along the trail. Several times, we’ve overheard lectures about the flora and fauna and the local history, and we have been envious even as we stood there eavesdropping.

Just below the Third Pass are the intricate, stone-step-thick ruins of Phuyupatamarca, through which the trail passes. This is a good warm-up for what we now face: Something like 3,000 steps from the Third Pass to the Trekker’s Hotel, where we plan to camp on our last night on the Inca Trail. The trail here passes through cloud forest as lovely as anything we have seen so far. Orchids in full bloom line the way, and several species of hallucinogenic hummingbirds flit around, sucking nectar from brightly colored bromeliads. I absolutely cannot believe I don’t have any pot or acid with me.

Yet, I can scarcely concentrate on the surrounding beauty, and the excitement of being spitting distance from Machu Picchu has dissipated into a torrent of pain covering every corpuscle from my quads to my tootsies. Gay, likewise, is one hurting unit. As a matter of fact, everyone on the trail by this point is wincing with every step. It has been more than a day since our last piece of dirt tread; everything since the Second Pass has been rock solid. And the sheer verticality of the descent is brutal. No switchbacks. Straight down, step after step after step. It’s like the stairway to Cirith Ungol that Gollum leads Frodo and Sam on. Except that, unlike Gollum, Frodo and Sam, we are going down. And here’s the main thing: These Incas must have been some short-legged people, because these steps are less than one-hiking-boot’s-worth deep and about four inches high. So, a man of regular gringo height has to choose between taking baby steps hour after hour or taking the steps two or three at a time, risking an ass-over-teakettle kinda slip that likely wouldn’t reach its logical conclusion for several captivating minutes.

By the time we reach the Trekker’s Hotel, our quads and calves are so shot, we are having trouble even lifting our feet. The descent into the Trekker’s Hotel ruined me, even more than my many descents into Mexico’s Copper Canyon and the Grand Canyon. I would kill for just one fucking switchback.

The hotel complex is a borderline civilized amenity. There’s a restaurant that serves decent food and more importantly, beer. Lots and lots of beer. There are indoor restrooms, some dingy dorm rooms, pay showers and several dozen terraced campsites. The one we picked out necessitated a stroll through a campsite already dibbsed by a tour company. It had the benefit of being close to the restaurant, should thirst require multiple journeys to and from camp (which ended up being the case). The resident guide scowled and said we couldn’t camp there. I scowled back and invited the diminutive lad to try and stop me. I thought his goddamned head was going to explode from anger, but he said nothing. Later, I bought him a beer and, from that moment on, I was his best friend. He even courteously pointed out to me the place located, sad to report, behind a rock scant feet from the front of our tent, where all the guides like to squat (despite the proximate indoor plumbing) when they pass through. And I thought it was my funky hiking socks that were befouling the air. Man, was I ever relieved to learn it was piles of nearby guide caca instead!

Gay and I did muster the energy to stiff-leggedly stroll down to the nearby ruins of Wiñay Wayna, which were only partially excavated and which looked like a giant, terraced baseball stadium. Despite our leg pain, we were overcome, for about the 200th time since we left Kilometer 88, with the unrivalled, multi-tiered grandeur of this place. I mean, these Incas could build some shit. How on earth could folks as dialed-in as the Incas seemed to be lose a home game to a couple hundred conquistadores? And, more importantly, how can we import some of this construction consciousness into the States, where a high percentage of new construction looks like it was designed by a frugal kindergartner and built with the specific intent of turning into compost within about 15 minutes of the last nail being driven in? Planned obsolescence did not seem to be part of the Incas’ building code.

Soon after hitting the hay, my stomach knotted up at the thought that we were now only a few hiking hours away from a place I had waited my adult whole life to visit. Shortly after that thought dissipated, I realized it wasn’t the notion of finally visiting Machu Picchu that caused my stomach to knot up. I was getting sick. Fast. My belches tasted very much like the fake bacon bits that 1) had been “aging” in my food bag since the previous summer (or maybe it was the summer before) and 2) I had sprinkled liberally upon my delectable freeze-dried dinner.

There’s a locked gate just past the Trekker’s Hotel, which the local constabulary doesn’t open till 5 a.m. It’s every Inca Trail hiker’s plan to arrive at Intipuncu, a small ruin with a perfect view of Machu Picchu, at dawn. It was still dark when we arrived at the gate, which was good, as I found myself having to run off the trail several times to befoul the turf. In my condition, I hiked slowly — too slowly to make it to Intipuncu by dawn, which we likely wouldn’t have done anyhow, given the fact that our legs couldn’t have been any stiffer had we strapped two-by-fours to them.

Then, there it was, two miles away, just like we had seen in hundreds of photos over the years: Machu Picchu, the only abandoned city in the Western Hemisphere that can rival Guatemala’s Tikal, which Gay and I have visited twice. The large tribe of Inca Trail hikers gathered at Intipuncu all agreed: Seems a lot smaller than we expected! Indeed, Machu Picchu looked tiny, even inconsequential from this distance. Just as we were prepared for the kind of let-down that often arrives at the seminal moment of any dream trip, the overcast sky opened up and a large stream of sunlight hit the ruins directly, and the entirety of South America’s most-famous archeological site glowed orange and yellow, like it was spiritually radioactive. The tribe gasped as one. It was like, “OK, we’ll all just shut the fuck up right now and feel humbled.”

It took 45 minutes to reach the outskirts of metro Machu Picchu. It got larger and more grandiose and more powerful-feeling with each step. We arrived at 8 a.m., by which time I was feeling very, very poorly. Unlike most of our trail brethren, who only planned to stay half a day at the ruins before returning to their long, windy journeys to wherever, we had planned to spend three or four days exploring Machu Picchu. There’s only one hotel at the ruins, which costs about a million dollars a night. So, we hopped one of the frequent buses for the 30-minute ride down (way, way down) to the aforementioned hamlet of Aguas Calientes. We got a nice room for about $5 a night and I basically slept the rest of the day away. By evening, the rotten fake bacon bits had enthusiastically egressed my premises (much to the chagrin of the local plumbing, which was up to general Latin American standards), and I was feeling fit.

We spent the next three days, 12 hours a day, savoring every molecule, every nook and cranny, every perceivable nuance of Machu Picchu, flat-out one of the world’s best backpacking destinations, which is a weird thing for me to say, much less feel, as, for the most part, cultural sites don’t excite me as much as raw, untrammeled wild country, places where evidence of human habitation, even visitation, are few, if not non-existent. But there are assuredly a few works of man that are every bit as stunning, powerful and flat-out wonderful as the deepest canyons or the wildest deserts. There’s Tikal and Angkor Wat, places that have the added benefit of being located in country wild and remote and wildlife infested enough that, even without the world-class works of man that lie within their heart, they would be worth a 100 visits. And there’s the Pyramids of Egypt, and maybe even Notre Dame and maybe even the Empire State Building. Despite our many flaws, we are surely capable of producing Beauty, with a capital “B.”

All of our fellow trail hikers had moved on, but, every day, a new batch came in, dirty, limping and with the kind of gleam in their eyes that only comes from taking the hard way to a cool place. There was definitely a hierarchy within those indescribable ruins: There were those who had walked there and those who did not. That’s exactly the way it should be.